canal (E)

canal (F)

canale (I)

kanal (g)

Canal (P)

industrial canal, new orleans, louisiana

If you were a contestant on the 1980’s American game show Family Feud, hosted by Richard Dawson (best known for playing Corporal Peter Newkirk on the television show Hogan’s Heroes-yes, everything gets tied back to World War II) and the question was top five canals or places famous for canals, the “survey wouldn’t say” the New Orleans Industrial Canal. The survey would likely say: Venice, Italy; Amsterdam, Netherlands and all the Dutch canals; the Panama Canal; the Suez Canal: the Rideau Canal, Ottawa, Canada; Annecy, France, known as little Venice: or even the canals of Birmingham, England.

But the Industrial Canal (whose official name is the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal) has a fascinating and terrible history. First, some orientation to its location and the geography of New Orleans. New Orleans is the most famous city in the U.S. state of Louisiana, even though it’s not the capital, that’s Baton Rouge. It’s known for great food; music, especially jazz (Louis Armstrong, the famous trumpet player was born there as well as all the Nevilles and Harry Connick, Jr.); and its celebration of Mardi Gras or Fat Tuesday, the end of the carnival celebration which takes place on the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent, traditionally a time when Christians fast or at least give up eating some of their favorite items.

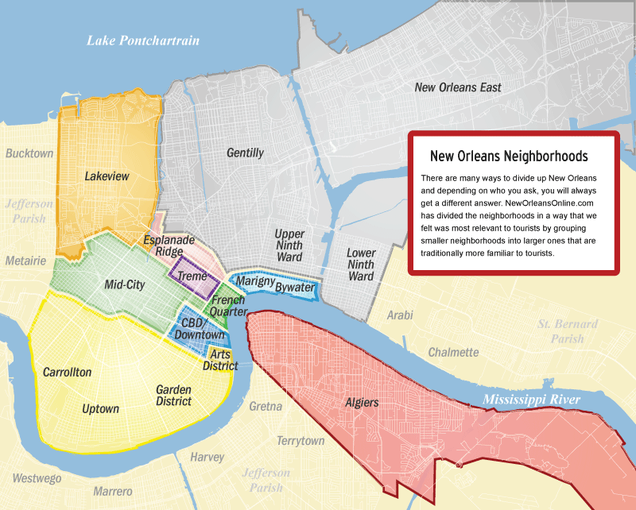

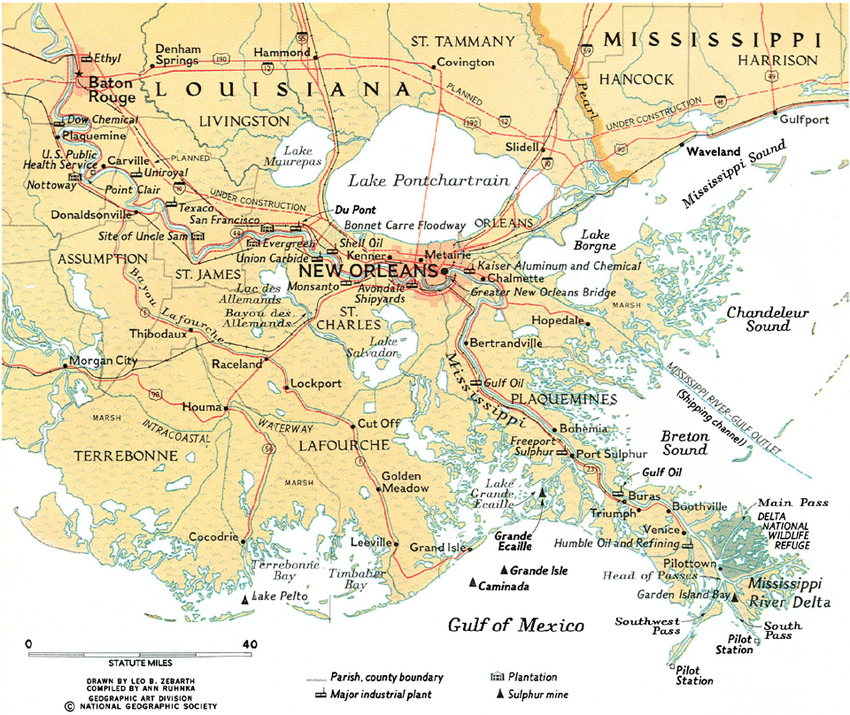

Looking at the map of New Orleans neighborhoods, the Industrial Canal is the body of water running along the eastern side of Gentilly, separating Eastern New Orleans from the rest of the city; separating the Upper and Lower Ninth Ward; and connecting Lake Pontchartrain with the Mississippi River. Half of the canal’s length is also part of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. It can be confusing in New Orleans, because, if you think of a map of the United States, the Mississippi River flows south into the Gulf of Mexico. But in New Orleans, the river flows west to east with some sharp turns. So, in New Orleans, if you are heading Uptown or up the river, you are heading west, and if you are heading down the river, you are mostly heading east. The Mississippi River continues flowing past New Orleans, east and then south, another 250 miles, into the Gulf of Mexico. It’s a long trip up and down the river with a lot of hazards. While the map below is a bit outdated, it illustrates how bypassing the long trip up the Mississippi River and getting to New Orleans via Lake Borgne and Lake Pontchartrain or via the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet (more on that below) would be very advantageous.

Even back in the 1820s, officials started thinking about ways ships could bypass the long trip up or down the Mississippi River. The idea was to connect Lake Pontchartrain to the Mississippi River and connect Lake Pontchartrain to the Gulf of Mexico, creating a faster route. There was another benefit to building a canal through the city: creating waterfront property where none had existed before. And it was property that wasn’t subject to the restrictions that applied to property along the Mississippi River.

It took until 1918 until work began on the canal, under the direction of engineer George G. Goethals, the chief engineer for the Panama Canal locks, and a familiar name for you New Yorkers and New Jerseyites as he is the namesake of the Goethals Bridge, which connects New Jersey and Staten Island, New York. Do you know that the word for what a resident of a particular place is called is a demonym? This was a new word for your host.

In 1923, the 5.5-mile canal opened, connecting Lake Pontchartrain to the Mississippi River. At the river end is a 640-foot-long lock, which mediates the difference in water levels between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, allowing small cargo ships and mostly barges to traverse from the lake to the river and access all the infrastructure along the Mississippi River. The canal is 30 feet deep and 300 feet wide at its lake end and about 150 feet wide at its lock end. Since it was built, there have been multiple campaigns to widen the lock, with lots of opposition to the widening. The completion of the canal brought industrial development and jobs to the area around it, leading to increased settlement of the Lower Ninth Ward.

The 1960s saw the completion of another major navigational project in New Orleans: the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet Canal (aka MRGO or MR-GO). MRGO was a 76 mile long, 600 feet wide channel constructed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers to again shorten the route between the Gulf of Mexico and the Industrial Canal. It allowed larger ships, which wouldn’t be able to get through the lock from the Mississippi River to the Industrial Canal, to still access the canal. But there was a huge problem from a hurricane/storm surge protection point of view. MRGO was a channel cut through the marshlands of Eastern New Orleans through which storm surge could, well, surge, into the Industrial Canal and greater New Orleans. The construction of MRGO destroyed over 27,000 acres of wetlands which had acted as buffer from storm surge. As a resident of New Orleans, instead of having a sponge to your east soaking up storm surge, you had an alley that would funnel water right into the city. Given its environmental impact, the project likely wouldn’t be approved today.

A few years after the completion of MRGO, in September 1965, Hurricane Betsy hit Louisiana as, what was later upgraded to, a Category 4 hurricane. The hurricane drove a storm surge into Lake Pontchartrain and MRGO. Levees for MRGO and on both sides of the Industrial Canal in the Lower Ninth Ward failed. Eighty percent of the Lower Ninth Ward area went under water and hundreds of people may have lost their lives; the city reported an official count of eighty–one deaths. The flood water reached up to and over the eaves of houses in some places in the Lower Ninth Ward. Some residents drowned in their attics trying to escape the rising waters. Wait, didn’t this all happen during Hurricane Katrina in 2005? Yes, but it also happened in 1965. It took 10 days for the water level to recede and approximately 164,000 homes were damaged or destroyed.

And then, in 2005, it happened again. On August 29, Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana as a Category 5 hurricane and levees on both sides of the Industrial Canal failed, flooding the entire Lower Ninth ward as well as the cities of Arabi and Chalmette in neighboring St. Bernard parish. One of the failures occurred in the same area where the levee failed during Hurricane Betsy. There were over 1500 fatalities. After the storm, investigation and computer modeling estimated that MRGO intensified the surge, raised the height of the surge by almost three feet and increased its speed by 5 feet per second in the area where MRGO met the other waterways.

After Hurricane Katrina, the MRGO was closed. A permanent storm surge barrier was constructed in MRGO in 2009, and the channel has been closed to maritime shipping. Closer to New Orleans, a 1.8 mile surge barrier, costing more than $1 billion to build, was constructed to prevent future storm surges from penetrating into the inner harbor of the Industrial Canal and Intracoastal Waterway. The barrier, the largest of its kind in the United States, protectz against storm surges up to 28 feet in height. And the Lower Ninth Ward? Well, it’s not what it was, having lost a lot of its population. There were about 14,000 people living there in 2000. After Hurricane Katrina, in 2010, there were only about 2800 people living there. Imagine if your town or city lost almost 3/4 of its population after one event.