forzada/forzado (s)

gezwungen (G)

forçado (P)

dragoon(ed) (E)

obligé (F)

mount faron, toulon, france

We don’t usually discuss the definition of the Word but this one is a little tricky, so we’ll make an exception. The meaning of our Word in English is dragooned or forced. Yes, you’re thinking, wait, a dragoon is a type of infantry who rode horses but then got off the horse to fight on foot. (Well, maybe one or two of you are thinking that.) But there is another meaning for dragoon. It means to force or coerce someone into doing something. And that is the meaning we are using today.

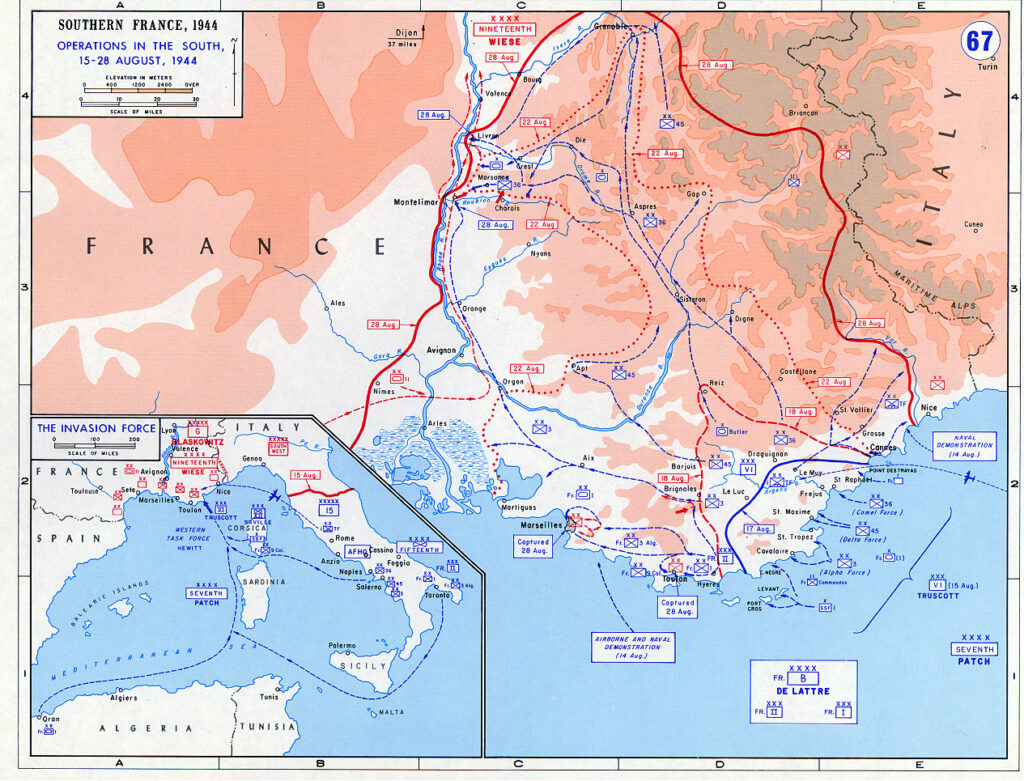

In an earlier post, we talked about two major World War II campaigns by the Allies in Europe in 1944: the D-Day invasions into Normandy in June 1944 (known as Operation Overlord) and the invasion into the Netherlands in September 1944 (known as Operation Market Garden). But there was a third major invasion into southern France, in August 1944, that is not as well known: Operation Anvil, renamed Operation Dragoon on August 1, 1944, partly due to the fact that Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of Britain, was opposed to the operation and felt “dragooned” into approving it. More on that later.

Mont Faron is a mountain which overlooks the city and harbor of Toulon on the southern Mediterranean coast of France, east of Marseille. It’s almost 600 meters tall and from its summit has an incredible view of the Var coast and the surrounding countryside. The summit is reached either by a one-way road (once you start up on the west side of the mountain you must continue to the top in order to then descend on the eastern side) or by cable car or as the French call it: le téléphérique.

At its summit is the Mont-Faron memorial, inaugurated by General de Gaulle on August 15, 1964, and dedicated to the memory of the French men and women involved in the D-Day operations and the liberation of Provence, including Toulon. As the Normandy invasions were fought mainly by American, British and Canadian troops, the fact that Operation Dragoon was fought mainly by the French soldiers of General de Lattre de Tassigny’s Army B was considered by the French to be an important contribution to the war effort. As the website of the memorial states, “France liberated itself.”

Operation Anvil was originally meant to coincide with the D-Day invasion in June 1944 but had to be scrapped due to lack of troops. Resurrected as Operation Dragoon, the plan was opposed by the British. Winston Churchill thought it would divert resources from the ongoing battles against the Nazis in Italy. He favored an invasion from northern Italy near Trieste, into what is now Slovenia and Croatia, northward to Austria and Hungary. He argued such an invasion could cut off Nazi fuel supplies and prevent the advance of the Russians too far into Eastern Europe. Churchill was dragooned into supporting the Provence invasion by pressure from General De Gaulle, the head of Free France, seeking the opportunity for a direct attack by French troops and by pressure from the Americans to gain new ports, other than those in Normandy, by which to supply their needs. Eventually, Operation Dragoon was scheduled for August 15, 1944.

The American troops involved in the operation were three infantry divisions from Major General Lucien Truscott’s US VI Corps. Airborne troops were from the American 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment and the British 2nd Parachute Brigade Group. The US eight Fleet provided the seapower. The French forces, under the commander of French Army “B”, General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, included the French II Corps, with the 1st, 3rd (Algerian) and the 9th (Colonial) Infantry Divisions. More on them below.

All of the troops on the Allied side were experienced and well supplied. By contrast, the German troops were either inexperienced or battle-worn and troops had been diverted to the battles in Northern France. The operation was successful with American and French troops able to head north up the Rhone River valley by the end of August, 1944. For a detailed description of the operation, try reading the article by Dr. Chris Rein on the website of the National WWII museum.

So what about French Army “B”, which later became France’s “First Army”? Where did they come from? Well, mostly from France’s colonies in Africa, including Algeria, Morrocco, Tunisia, Senegal, Chad, and Cameroon, among other areas. They were known as tirailleurs. Of the approximately 250,000 members of Army “B”, between half and 80 % of them were from Africa. Despite the success of Operation Dragoon, the African troops did not always receive credit for their contributions and in fact, later in 1944, they were being withdrawn from units in favor of resistance fighters from the French Interior Forces, who happened to be white. Some colonial soldiers spent the winter of 1944 in transit camps. There is also evidence that there was pressure from American and British forces to “whitewash” the troops who liberated Paris in August 1944. (Remember that during World War II, American white and black soldiers were segregated, assigned to separate units.) No black soldiers were assigned to the troops who marched down the Champs-Élysées during the liberation of Paris. The 80th anniversary of Operation Dragoon has focused attention on the treatment of France’s colonial soldiers during and after the end of World War II.