vulcano (I)

volcán (S)

vulkan (G)

vulcão (P)

volcano (E)

Mount Pelée and St. Pierre, martinique

We’re going to leave discussion of the two deadliest volcano disasters in modern times, the 1815 eruption of Tambora and the 1883 explosion of Krakatoa, for other posts. (For a wonderful children’s book about the Krakatoa explosion, try to find The Twenty-One Ballons by William Pene du Bois.) And we will talk about Mount Vesuvius, or Vesuvio as the Italians call it, the volcano which buried the now famous town of Pompeii in 79 CE.

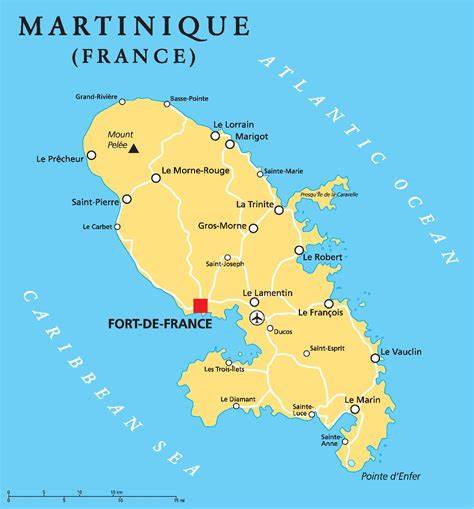

But first, your host would like to focus on the third deadliest volcano disaster in modern times, one which isn’t very well known. St. Pierre is a town on the northwest coast of the French island of Martinique in the Caribbean. Martinique is not only a French island but (along with the neighboring island of Guadeloupe) a French department, which means it has the same political status as such mainland French departments as Manche, Var or Savoie. One of Martinique’s claims to fame is that it was the birthplace of the Empress Josephine, wife of Napoleon I. Slavery was abolished on the island in May 1848 after a major revolt, days before a proclamation which abolished slavery arrived from France.

St. Pierre was not the capital of Martinique (that would be Fort-de-France) but in 1900, it was known as the “Paris of the Caribbean.” It had a large harbor protecting ships full of sugar and rum, Martinique’s prime exports; and it was the commercial capital, with four major banks located in St. Pierre. Unfortunately, St. Pierre lay at the bottom of the slopes of a massive volcano, Mount Pelée, which rose almost 1400 meters above the city. Pelée was thought to be, if not extinct, very quiet. It had made a few noises back in 1792 and had spewed ash on northern Martinique in 1851 but in 1902, it had been quiet for fifty years.

The first signs that Pelée was waking up came in April 1902. There were tremors in St. Pierre and sulfurous fumes floated down from the mountain. On May 2, 1902, there was a small eruption at the top of Mount Pelée which lit up the night sky. The next day, residents found dead birds that had fallen from the air, weighed down by ash. The level of the Rivière Blanche, which drained from Pelée’s southwest flank into the sea north of St. Pierre, began fluctuating wildly, sometimes overtopping its banks. People who lived close to or literally on Pelée began arriving in St. Pierre, which officials (wrongly) said was safe.

On May 5, a 100 kilometer per hour lahar (a mixture of lava, mud, debris, and hot water) came down the Rivière Blanche and destroyed a sugar processing plant, killing almost two dozen people, on its way to the ocean, where it produced a 3-meter-high tsunami that inundated St. Pierre. According to personal accounts, Mount Pelée’s shaking disturbed insects and snakes, some of whom, being very large and dangerous, killed livestock and people. On May 6, blue flames could be seen as a lava dome reached the top of Pelée’s crater rim. On May 7, a commission appointed by the island’s governor stated that Mount Pelée was not dangerous. St. Pierre’s residents continued to go about their business.

But on May 8th, Mount Pelée exploded, and a cloud of gas, lava, debris, and water obliterated St. Pierre in minutes. Almost all of St. Pierre’s residents, close to 30,000, were killed from suffocation and burns, including the island’s governor who had come from Fort-de-France to reassure St. Pierre’s residents. For days, St. Pierre and the ships in its harbor burned. The only survivors were a shoemaker and a prisoner who was saved by his position in a jail dungeon with only a single window.

Even after the May 8th explosion, Pelée continued to be active. On August 30, an eruption destroyed the village of Morne Rouge, killing another 1,000 to 1,500 people. And, amazingly, an obelisk-shaped lava spear/dome rose from the crater during the rest of 1902. According to reports, it was about 100 meters wide at its base and grew at impressive rates. It supposedly rose 10 meters in eight days and 6 meters in four days, and, at its peak, towered 350 meters above the rim of the crater. Molten lava could be seen inside the obelisk, which lasted until the spring of 1903. Mount Pelée had a sustained period of eruptions between 1929 and 1932 but, since then has been quiet. St. Pierre was rebuilt and is a small town. Mount Pelée is still monitored with a network of seismometers.

Mount Vesuvius towers over the city of Naples, Italy. Vesuvius has erupted many times since it buried Pompeii in lava and ash more than 2000 years ago. It’s the only volcano on Europe’s mainland to have erupted in the last hundred years. Since more than 3,000,000 people live near enough to be affected by an eruption, with at least 600,000 in the danger zone, it is regarded as one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. It is also one of the most monitored volcanoes in the world, not surpisingly, as the Naples area is the most densely populated volcanic region in the world.

There aren’t too many fun facts when it comes to volcanoes but here are two. From 1880 to 1944, there was actually a funicular, the Vesuvius Funicular, which took tourists up Mount Vesuvius.

To commemorate its inauguration, Luigi Denza wrote a Neapolitan Song, Funiculì funiculà. You know this song even if you don’t think you do. It’s been sung by tons of singers including Mario Lanza, Connie Francis, Andrea Bocelli and even Luciano Pavarotti. And you’ve heard it sung on the Seinfield tv show during Elaine’s driving trip around New York with the Maestro, aka ????. For a really fun, brass version of the song, try Napoli, adapted by Herman Bellstadt, a cornet player who emigrated to America from Germany and was known as the “Boy Wonder.”